New Research From Binghamton University Could Lead To Improved Method of Treating Pancreatic Cancer

Binghamton University

The State University of New York

By John Brhel

March 23, 2018

Edited For Style and Length of Content

Combination Heating and Freezing Kills Pancreatic Cancer Cells

A heating and freezing process known as dual thermal ablation can kill pancreatic cancer cells, according to new research from Binghamton University, State University at New York.

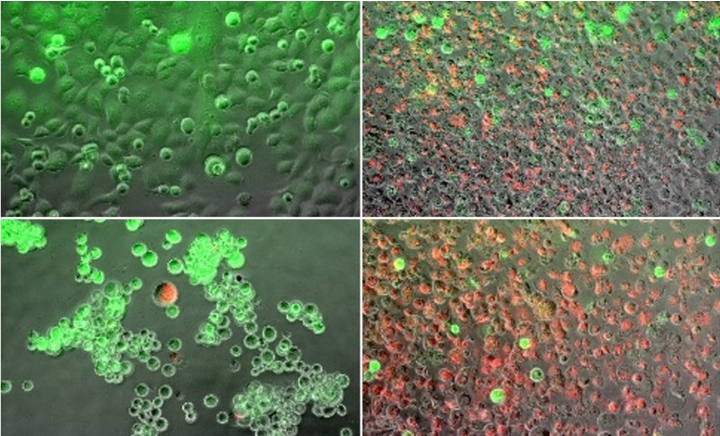

Pancreatic cancer cells stained with live/dead fluorescence dyes, with live cells in green and dead cells in red. Pictured are control cells (top left), frozen cells (top right), heated cells (bottom left) and DTA treated cells (bottom right).

The collaborative study, conducted by researchers from academia and industry and funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute, used pancreatic cancer cells to investigate the effect of heating and freezing on cell death. The research was conducted by Robert Van Buskirk and John Baust, professors of biological sciences and directors at Binghamton University’s Institute of Biomedical Technology, and Kenneth Baumann, a graduate student studying biology.

“How do we solve the problem of pancreatic cancer when it comes to trying to get rid of the tumor, when chemo and radiation just simply doesn’t work?” said Van Buskirk. “The whole idea is, can one come up with a different surgical intervention that’s less invasive and more effective?

“In order to figure that out, you can commercially obtain pancreatic cancer cells and grow them on specialized plasticware,” Van Buskirk said. “The basic question is, are both freezing and heat in combination more effective than freezing or heat alone? If you freeze pancreatic cancer cells like you do in cryoablation, a lot of them die, but some will survive and regrow. If you heat them, they’ll die, but again some will come back. But with dual-thermal ablation, for reasons that we do not yet understand, more die and don’t come back. In fact, over time, cells that survive the initial insult continue to die.”

“What we’ve observed is that we are able to achieve complete cell death using a combination of heating and then freezing at temperatures that alone would not be lethal to kill pancreatic cancer cells,” said Baumann.

Researchers heated and froze cancer cells and looked at the effect, using various technologies to determine the level of cell death, on regrowth as well as which cell stress pathways were activated.

“When cells are disturbed—which means they are frozen or they see heat—various cell stress pathways are activated,” said Van Buskirk. “The interesting thing about cells, especially cancer cells, is that they will activate pathways to protect themselves. The objective of this line of molecular-based research is to find out which stress pathways are activated in pancreatic cancer cells so that we can better understand why dual-thermal ablation appears to be more effective.”

“Current studies are focused on elucidating which stress pathways specifically cause these cells to die or what is keeping them alive. That way, we can optimize this treatment to be as effective as possible against pancreatic cancer,” Baumann said.

According to Van Buskirk, modulating these stress pathways is the key to making the heating and freezing ablation process more effective. This could lead to the development of a new way to remove cancerous pancreatic tumors.

In addition to the cell molecular research, several members of the study team are working on developing new catheter technologies to deliver this ablative therapy to patients. “If a very thin catheter can be developed to target the tumor, and if we understand how pancreatic cancer responds to ablation at the molecular level, then we may be able to develop a new therapy to approach something that has been completely unapproachable, the targeted killing of a tumor in a very difficult place: the pancreas,” said Van Buskirk.

The article, “Dual thermal ablation of pancreatic cancer cells as an improved combinatorial treatment strategy,” was published in Liver and Pancreatic Sciences.